Stereo-Viewer (2023)

Installation from Flashlights

The work consists of a found Stereoscopic 3-D slide viewer and a wooden functioning replica I made.

Inside my viewer are stereoscopic slides I photographed of 3-D archivists Susan Pinsky and David Starkman in their home.

I found this antique stereo-viewer at an estate sale in Santa Monica in February 2022. It was sitting on the floor of an old garage workshop. Its power cord had been chopped off so I couldn’t plug it in to see what it did. Nobody at the sale knew what it was.

I reluctantly paid $40 for it and brought it home to try and fix it.

Opening it up revealed a complex mechanism with a drum of 12 different stereo slides. The left button on the front activated two lightbulbs, which backlit the slides. And the right button activated a motor, which automatically advanced the drum to the next slide. I soldered on a new power cord and plugged it in.

I was baffled by what I saw. 1950s women posing nude with mechanical components and signs advertising their features.

Mundane photos of engineers machining the components in a factory were mixed in with the nudes.

The backlit 3-D slides simulated the sensation of actually looking at something in front of me closer than any 3-D film or VR I’d experienced.

I didn’t know what to make of the thing. I couldn’t tell if it was a real advertisement with a peep show, or a peep show posing as an advertisement.

The handwriting on the viewer matched the handwriting on the signs in the photos, which linked the viewing apparatus with the photographs. It suggested to me that the machine was made by the same person who made the photos.

While disassembling the viewer I found a sticker that left contact information for its maintenance. Geo Mann.

Searching online for “Geo Mann 3-D” lead me to a webpage about “George Mann” on a stereo photography enthusiast’s 3-D hall of fame website.

Susan Pinsky, 1977

The webpage, made by a woman named Susan Pinsky, told a personal story about finding a similar viewer at a flea market in 1977.

In December of [1977] we went to a "Swap Meet" in the Los Angeles area. When we were looking around, at one point we saw a small box-shaped item with what looked like stereoscopic viewer lenses sticking out of it. Our hearts started to pound.

The seller explained to us that it was made by a neighbor of his who had passed away. We were able to open it up, to look inside, and could see that it had a rotating drum that would hold a dozen Stereo Realist size slides, held in place by a thick rubber band made from a tire tube. It had an electric motor to rotate the slide drum, and buttons on the front labeled "Hold to See" and "Press to Change".

The price was right, so we bought it right away. Then the seller told us he had more of these viewers in the garage of the man who had passed away. He told us the man's name was George Mann, and that he had made these viewers in the 1950s as a commercial enterprise. He also told us that George Mann had also been an actor, and was the model for "King Vitaman" on the cereal box.

We made a date to meet at the garage some days later. The garage, located in Santa Monica, California, faced an alley. We met the seller out front, and then drove around to the garage.

Inside there were about 35 of the same motorized 3-D sequential viewers. There were also pedestals, with cast iron bases, that the viewers could be mounted on, for viewing the slides while in a standing position. Everything was covered with a heavy layer of dust.

By then we had cleaned up the first viewer that we had bought, figured out how it worked, and loaded it with a dozen slides. While not easy to install the slides, once in place it turned out to be a very nice motorized sequential 3-D slide viewer! So we knew that we could do something with all of these viewers, if we could get them at a reasonable price.

In the end we bought all of the viewers. Because of their heavy weight and bulk, we only had the space in our car for one of the pedestals, which sank a couple feet deeply into the back seat of our car. It was a heavy item! (We found out later that the rest of the pedestals had been immediately sold as scrap metal).

Over the course of the next month we opened and cleaned all of the viewers, and tested them to be sure the motor was advancing the slide drum properly. Once that was done we put an illustrated ad in the February 1978 issue of "Reel 3-D News". We offered them at $40 each plus $4 shipping.

They must have sold quickly, because we never placed a second ad to sell the viewers!

I was amazed by the ways her story paralleled my experience finding the viewer. The page goes on to explain how Mann’s 3-D viewer enterprise worked.

The seller explained to us that George Mann had a business where he took 3-D slides of various scenic subjects, filled the viewers with images, and then rented them out to restaurants, doctors or dentists offices, bars, or other businesses to offer as a diversion while waiting for a table, or in the waiting room of an office. They were also used at Trade Shows. The viewers were designed to be mounted on the pedestals with a single hex bolt underneath. Every couple of weeks he would move each viewer from one location to the next, so that every location would have a fresh set of images for viewing every couple of weeks.

This confirmed my suspicion that the photographer and the viewer maker were the same person. George Mann made the viewing machines at the Lear Jet factory, which was at the end of the street I grew up on, next to the Santa Monica airport. That was also probably where the photos of the factory workers were taken.

The website was made by Susan Pinsky, a 3-D enthusiast. She and her husband David Starkman operated a 3-D mail order catalogue and magazine for many years. I was shocked to find out the page was only a few years old, and Susan was still actively adding to it.

I became just as fascinated with Susan and David as I was with George Mann. I knew they lived nearby me and I wanted to reach out and meet them.

I drafted an email to them a few times but for some reason never sent it…

A year later I brought the viewer to show David Wilson, the person I knew who knew the most about 3-D, and founder of the Museum of Jurassic Technology. I used to work there, and the viewer reminded me of one of the 3-D viewers they have on display at the museum.

It shows black and white stereo cards instead of Kodachrome backlit stereo slides, but the rotating drum mechanism was so similar to George Mann’s. I wondered if David had seen one of Mann’s viewers before.

David looked at the viewer and he told me about the Stereo Realist camera that the photos were taken with. I was leaving on a trip to Japan the next day, and he insisted I take his old Stereo Realist with me so I could take 3-D photos on my trip.The idea of shooting my own stereo photos hadn’t occurred to me until that point. He went off to look for the camera… but it was nowhere to be found.

He said that he didn’t know anything about George Mann, but he knew who would: Susan Pinsky and David Starkman. I told him about how I’d actually found their website.

Susan Pinsky and David Wilson at the Museum of Jurassic Technology via Susan Pinsky’s Flickr

He said they were old friends of his.

They even contributed an exhibit of 3-D “vectographs” to the museum once.

David Wilson, center via Susan Pinsky’s Flickr

He attended their Viewmaster club meetings in the ‘70s, long before he founded the museum.

He told me that Susan and David lived nearby and had a huge 3-D collection in their home. He helped put me in touch with them via email. They were interested in seeing my viewer, because they only knew of one other example of a Mann viewer that wasn’t part of the ~35 they restored and sold in 1977, with its original slides intact. We made plans to meet up after I got back from my trip.

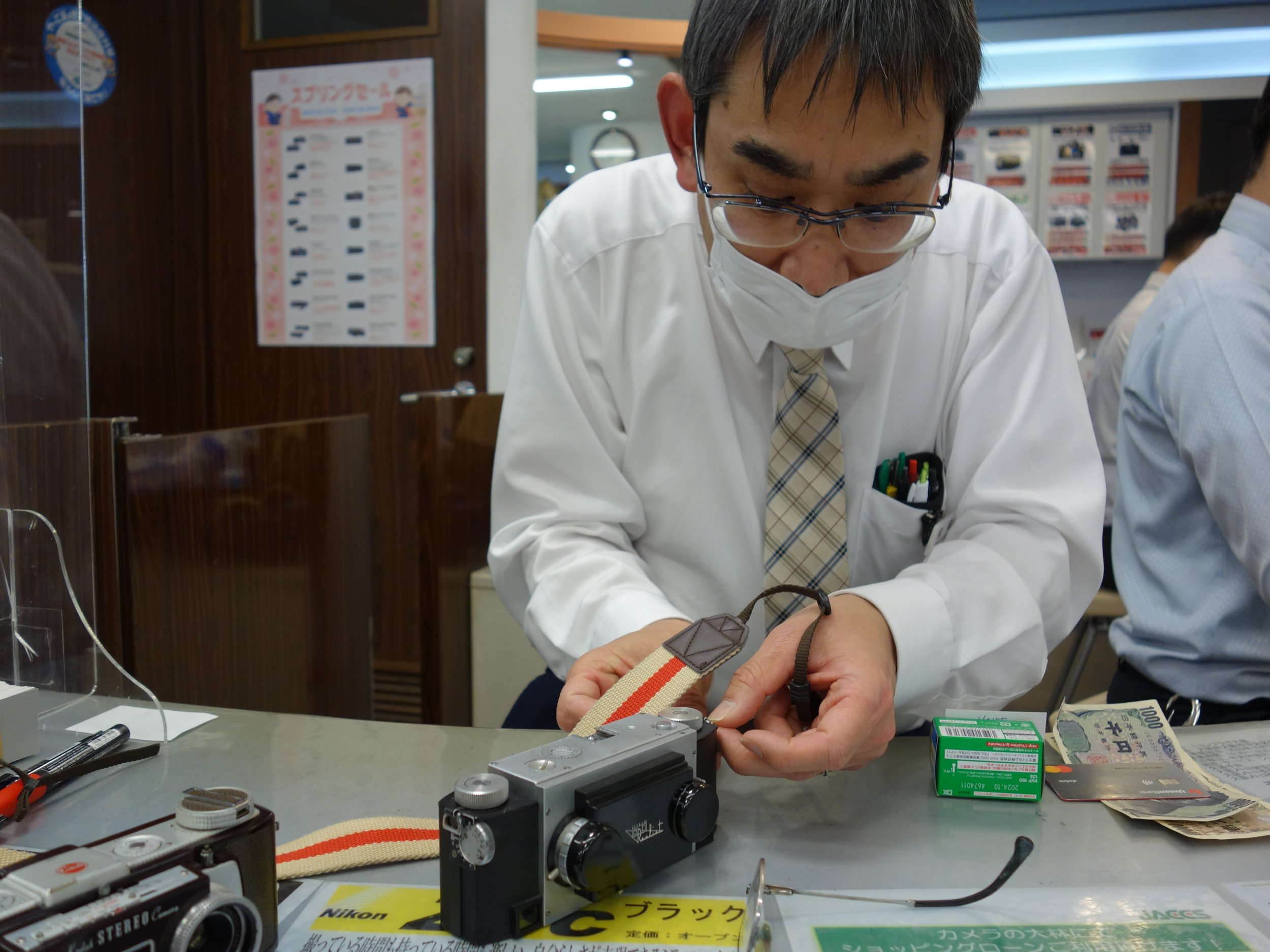

A few days later in Osaka, Japan, I stumbled upon a used camera shop and spotted a shelf of stereo 35mm cameras.

I ended up buying my own Stereo Realist, the same model that George Mann and David used.

Now with a 3-D camera on my hands, the question about how to show the 3-D photos came. 3-D photos did not translate well on screens. Part of what excited me about finding Mann’s viewer was the necessity of the complicated apparatus just to view the slides. The viewer itself was as much a work of art as the photos.

After I got back from my two month trip, I began an attempt to replicate Mann’s 3-D viewer. I carved an eyepiece in the shape of the original cast metal one using basswood.

I set up a time to meet Susan and David at their house and show them my viewer.

Their house was like a 3-D museum.

Their collection of viewing devices spilled into every room, even the bathroom.

Susan and David own two George Mann viewers. They used to have a third, but they gave it to George Mann’s son, after discovering that he didn’t have one.

Their viewers didn’t contain slides when they got them, so they’re filled with a variety of slides they’ve photographed, and others from their collection.

Their collection contains other 3-D collections bestowed to them by colleagues who have passed away. They steward these collections by archiving and digitizing them.

Susan began her 3-D hall of Fame website a few years ago to offload her 3-D archive online. She used Wix, a free website service, so that it could live on in perpetuity after she passed. She's one of only a handful of archivists digitizing 3-D slides and sharing them online. During COVID she dedicated most of her time to building the site. However, she recently reached a limit on JPEG files she could add before Wix charges a subscription fee. This has halted her work on the site.

Their house was also a museum to their relationship. They’ve been together for 50 years, and shared a passion and ran a business together for most of those years. They never had kids. Their work was what they dedicated their lives to. I asked them what their plans were for their collection after they died. Their families weren’t interested in taking on their things, so their plan is to donate it all to a photography museum and friends.

We spent the entire day together, and they took me out for dinner.

Inspired after our meeting, I continued work on my viewer.

After some experimentation I came up with a design for a drum that held 8 stereo slides. The slides were held in place around an octagon by rubber bands.

I made a holder to mount the drum so it could spin freely within the enclosure.

I cut holes in the drum holder for small light bulbs and added light reflectors (made out of bent pieces of soda cans) behind the slides, which backlight the slides. I loaded the drum with found stereo slides given to me by Susan and David, to test the viewer as I was building it.

Remaining faithful to George Mann’s original viewer design, I set out to motorize the advancement of the drum. It was the first time I had ever worked with motors before.

The motor made the machine much more complicated, and it was difficult to stop the motor right on a slide. I wasn’t confident in my ability to engineer the motor in a way that could operate reliably for as many years as Mann’s.

After some deliberation I dropped the idea of the motor and opted for a manual hand crank to advance the drum. I carved it out of a block of maple, in the shape of an octagon to communicate that there were 8 slides in the drum.

I mounted the lightbulbs, cleaned up the drum, and added a push-button switch to turn on the lights, and finally, the internal mechanism was complete.

Still remaining, however, was the question of what the photos inside the machine would be when I showed it at my upcoming art show in San Francisco. It was filled with odd found photos as placeholders, but I wanted to fill the machine with my own photos, taken with my new Stereorealist camera.

I made another visit to Susan and David, to show them the finished viewer. While there, I photographed them with my stereo realist camera.

These were ultimately the photos I showed inside the viewer at my art show.

The other works in the show were about collections and things left behind by people who died. The photos of Susan and David among their lifetime collection expressed these same themes.

The gallery sold the viewer, to my surprise, and I talked with them about changing the slides inside when it went to a private collector. The slides of David and Susan didn’t make much sense outside the context of the exhibition, so I replaced them with enigmatic found stereorealist slides I’d been collecting.